WASHINGTON — A U.S. Marine Corps unit spent seven months in the Indo-Pacific testing the service’s warfighting modernization effort, offering a glimpse at what future operations in the region might look like.

The 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit, along with the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group, spent its entire deployment, from November through June, in the area — the first time in more than 20 years that’s happened, according to the unit’s commanding officer, Col. Samuel “Lee” Meyer.

The 13th MEU used this opportunity to both focus on the challenges and opportunities that come with operating in such a vast region — with complex island chains and several nearby allies and partners — as well as identify which existing and emerging technology would best serve the force.

Meyer told Defense News that one particular focus involved experimenting with the Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations concept, and specifically pushing out small groups of Marines to establish so-called sensing expeditionary advanced bases throughout the region.

“The sensing EAB provided a risk-worthy, low-cost, low-footprint option to get eyes and ears on an area where the Navy may not be, or may not be able to maintain persistence,” Meyer said.

These sensing EABs could include 30-50 Marines who move ashore via aircraft or surface connector. They’d bring the security and logistics necessary to operate for a couple days or weeks away from the rest of the Marine expeditionary unit. They’d then get to work sensing the area around their beachhead and reporting back to the rest of the force.

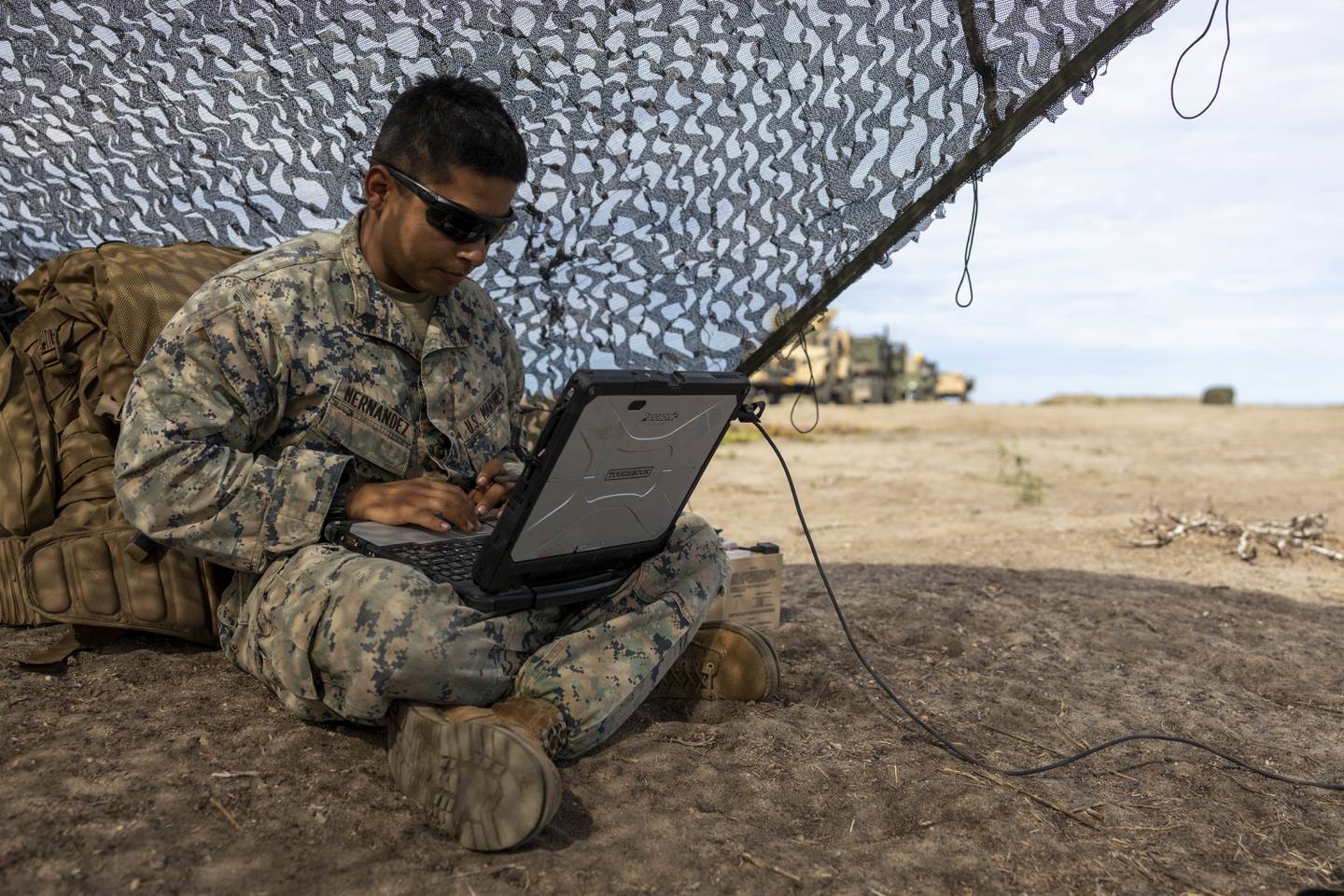

These Marines used commercial off-the-shelf tools, Shield AI’s V-BAT drone to provide live video feeds and Simrad Commercial boating radar to build maritime domain awareness in their corner of the ocean. That was sent back to the 13th MEU, the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group and the bridges of allies’ ships in real time to inform the actions of the larger naval force.

With the Marine Corps fielding new gear as part of its modernization effort, dubbed Force Design 2030, these expeditionary advanced bases may soon include long-range anti-ship missiles through the Navy/Marine Corps Expeditionary Ship Interdiction System program, or NMESIS.

But Meyer said his team was able to show that, with the right integration between his small units ashore and naval forces at sea, there would be several options for engaging enemy targets the sensing EABs find — including shooting Naval Strike Missiles off littoral combat ships.

Leaders of 13th MEU toured a littoral combat ship in Singapore. While they didn’t get to experiment at sea with the ship, Meyer said, they learned about the LCS configuration and capability, and brainstormed experiments for a future Amphibious Ready Group And Marine Expeditionary Unit, or ARG/MEU, including pairing the sensing EAB ashore with the vessel at sea.

They also discussed allowing Marines to use the LCS as a lily pad during long-range operations, landing on the ship’s flight deck for a brief time before resuming operations, or using large amphibious ships to refuel the much smaller littoral combat ships at sea. The Makin Island ARG did refuel the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer Chung Hoon in an experiment during the deployment, but there wasn’t an opportunity to try it with an LCS.

In the vast Pacific, “it’s all about logistics,” Meyer said. “And these [amphibious] ships are just a critical piece of that,” given their large fuel tanks, their aviation fuel, stores of dry goods and spare parts, and more.

The team also experimented with information tools, including an Amazon Web Services data analytics system. Meyer said the deployment proved the value of both the system and having young Marines onboard with additional skill sets, like coding — an follow-on effort from Force Design 2030 known as Talent Management 2030.

Experimentation also looked at broader integration of the ARG/MEU into the naval force — specifically the role of the Marine expeditionary unit’s F-35B jets and long-range MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft.

Carrier strike groups are expected to receive part-time access to a pair of their own CMV-22 Osprey variant for logistics missions, but the Makin Island ARG already had a full squadron of 10 Ospreys embarked for the deployment.

The Marine Corps is also ahead of the Navy in deploying F-35 Joint Strike Fighters; a full squadron of 10 F-35Bs operated from the amphibious assault ship Makin Island, whereas the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group — operating simultaneously in the Pacific — did not bring the fifth-generation fighter on deployment.

Meyer also noted that amphibious ships can access shallower waters than the carrier strike group, and the landing craft utility connector can reach shorelines inaccessible to almost anything else in the fleet.

“It highlights areas where we can do things that they simply cannot do,” Meyer said.

The Makin Island ARG and the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group conducted expeditionary strike force operations in February, both rehearsing operations with the amphibious forces supporting the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group in command, and rehearsing an amphibious raid operation where the carrier strike group supported the ARG/MEU in command.

During the operations, they used real aircraft in the air but synthetic terrain overlaid onto maps (Meyer said the force didn’t want to appear provocative by conducting a raid on a real island in the South China Sea). Makin Island served as the air defense lead and commanded all the Navy aircraft from the Nimitz for about 24 hours during the live-synthetic operation.

“We learned that there is a lot of value that Marine Corps and [its] ARG enablers offer to even a carrier strike group because there are things that they simply cannot do,” the colonel said.

However, some of the power of the Makin Island ARG and 13th MEU hinged on the makeup of the three-ship group. The amphibious assault ship (LHD) Makin Island was accompanied by the two San Antonio-class amphibious transport docks (LPD) Anchorage and John P. Murtha. An amphibious ready group would typically include one amphibious assault ship, one amphibious transport dock and one of the Navy’s aging dock landing ships (LSD).

Meyer explained that the LSD has a flight deck for helicopters to land and take off, but there is no hangar in which to store and maintain the aircraft. His configuration, with an LHD and two LPDs, meant each ship could have a “mini” Marine Air-Ground Task Force onboard — or a full complement of air, ground and logistics Marines that could disaggregate and perform missions without lacking a particular capability, or come together for larger operations as a full ARG/MEU.

That’s not possible with the LSD, which is unable to maintain an aviation presence onboard.

Meyer said the extra LPD allowed him to move helicopters off the Makin Island and make room for a full squadron of 10 Ospreys and a full squadron of 10 F-35Bs on the amphibious assault ship, creating a much more capable ARG/MEU.

While having two LPDs in the amphibious ready group will become the norm, assuming the Navy continues buying the LPDs or something similar, Meyer said deploying with this configuration now “gave me room to explore configurations in support of Force Design.”

Future ARG/MEUs will continue to experiment with different sets of aircraft and surface connectors, as well as new technologies, as the Corps tries to learn how to best implement the concepts behind Force Design 2030.

Broadly, Meyer said, “the sheer amount of capability that we have now compared to when I was younger is staggering. The amount of potential that we have is staggering. The amount of intelligence and energy from our young Marines, where everyone has all these ideas and people are willing to listen, try, fail, then learn, try again, succeed — it seems like there’s a much more open mindset from the service into getting it right, not just maintaining the status quo.”

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.